The Second World War 1939 – 1945

On Saturday 26 August 1939, Hitler demanded that Poland hand over Danzig and its corridor. Though war was not yet inevitable, the Regimental Adjutant received a call from Ottawa at 4:45 AM instructing him to call out the Regiment. Soldiers were dispatched to guard vulnerable points around the city; this was still a full two weeks prior to Canada’s declaration of War.

Early in November 1939, the Regiment learned it was not selected to be in the 1st Division. Many officers and men transferred to the Seaforth Highlanders or to the PPCLI to be sent overseas. In the meantime, the Regiment settled down to several months of monotonous guard duty. An interesting incident occurred when one young Rifleman on duty at Jericho Beach decided to create a little excitement. He fired his rifle into the cement and called out the guard claiming that held been shot at by saboteurs. The Guard was doubled. A ballistic expert from Ottawa examined the round which had been dug out of the cement at the Jerrico Air Base and declared it to be 9mm German. The Guard would have remained doubled if Lt Neil Pattullo had not managed to get the “true” story out of the sentry.

In June 1940 as the Allies lost the Battle of France and the British Army was evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk, the Regiment was finally mobilized as a unit of 4th Canadian Infantry Division. The Regiment concentrated at Westminster Camp in New Westminster for training. On 1 October 1940 the Regiment received word that it was to move to a secret destination “Overseas”. As they marched down 8th Street, one of the most famous and iconic photographs of the Second World War was snapped by Claud Detloff of the Vancouver Province newspaper when five year old Warren Bernard raced after his father, Jack, who poignantly reaches back for his son.

A large crowd saw the Regiment off aboard the SS Princess Joan. The “Overseas” destination turned out to be Camp Nanaimo, where they conducted further vigorous training.

In May 1941, the Regiment moved to Niagara-on-the-Lake, where they continued to train and helped to guard the Welland Canal. In November 1941, the Regiment moved to Debert, Nova Scotia where they continued training in the bitter winter conditions.

In January as the Regiment returned from their Christmas leave, it was announced that the Fourth Division would be converted to Armour, and the Regiment’s soldiers were converted from Riflemen to Tankers. The Regiment was designated as the 28th Canadian Armoured Regiment (British Columbia Regiment). Senior officers and NCO’s were sent to schools in Canada and overseas for training and the bulk of the Regiment sailing for England on 21 August 1942.

On arrival, the Regiment was sent to Elstead, Surrey, to continue their armoured training. There they participated in large scale exercises, such as “Spartan”, which involved the whole Canadian Corps in March 1943.

In August 1943, command of the Regiment passed to Lieutenant-Colonel Don Worthington, who had already had significant combat experience in North Africa where he was attached to the 2nd Lothian and Borders Yeomanry, a British tank regiment. By early October, the Canadian built Ram tanks the Regiment had trained on were being replaced by the new Sherman Tanks. These tanks were used by the western allied armies throughout the rest of the war.

Following the famous D-Day landings on the 6th June, 1944, the Regiment moved to France in late July 1944, and engaged in their first combat operations south of Caen, France in Operation Totalize, an operation initiated to break out of the Caen perimeter and force the German Army into retreat.

In Phase II of that operation, the 28th Canadian Armoured Regiment (BCR), as the lead unit of Worthington Force, set out to capture Hill 195 in the early morning hours of 9 August 1944. They carried out a fighting advance approximately ten kilometres south of Caen in Normandy, driving through the dark and smoke of the battlefield. When the eastern sky began to lighten early that fateful morning, the leading elements of the Regiment were disoriented passing through low ground with limited visibility; they were looking for high ground to occupy and defend. They did initially, and erroneously, report that they were on their assigned objective; however, they soon were able to orient themselves. When they could not use the radio to report their location they dispatched two different parties to provide their position and request support. Neither party was successful in getting word in time to any authority able to change the situation.

Fatefully, Worthington Force chose to defend high ground that was also assigned to a battle group of the 12 SS Panzer Division, consisting of a Panther tank battalion and a Panzer Grenadier infantry battalion. That German battle group was about to move onto the position when they got word that an Allied armoured force, Worthington Force, had beat them to it! That German battle group, reinforced by Tiger tanks from the famous 101st SS Heavy Tank Battalion, were the forces that the Dukes and Algonquians fought that day, along with troops from the 85th Infantry Division moving up from the south.

Given the strength, experience and fire power of the German forces that day, the soldiers of Worthington Force acquitted themselves well. They inflicted heavy casualties, maintained good discipline and carried out their basic battle skills with courage and conviction. The leadership was superb – Lieutenant-Colonel Worthington was cool, brave and set a superb example of courage and leadership throughout the day. His subordinate commanders, led by Majors Sideneous, Carson and Baron, were no less courageous and skillful.

As the day drew to an end without reinforcement or support, the defending soldiers conducted a fighting withdrawal, and most of the unwounded soldiers were able to return to friendly lines. They had lost half of their fighting echelon strength dead or wounded, as well 47 tanks.

That Worthington Force was unable to capture its assigned objective can be attributed to a number of factors. They were advancing into a position well prepared by the German defending forces. The pause in the advance the previous morning between Phase I and Phase II of Operation Totalize – to allow time for heavy aerial bombardment – had given the German commanders time to reorganize and redeploy their forces. Additionally, Worthington Force did not receive their orders for the operation until after midnight of 8/9 August and were unable to cross the start line until after 2:00 AM. That time compression did not leave them enough time to reach Hill 195 under cover of darkness. In fact, they achieved a breakthrough that, had it been reinforced and exploited, could have made a significant difference to the timing of the closing to the Falaise Gap.

However, fate dealt harshly with the Regiment that day. As in the First World War, they lost a brave and capable Commanding Officer and took heavy casualties in their first day of combat in the war.

28th CAR (BCR) was at history’s centre of gravity that day and they fought with distinction in the most famous place in the world in August 1944 – the closing jaws of the Falaise Gap. That action ended with one of the most devastating encirclement operations inflicted on the German Army in the Second World War. They fought with courage, skill and discipline.

A number of officers and men were always left out of battle in case of disaster, to form the nucleus of the Regiment. Five days after coming perilously close to total destruction, the 28th attacked again and this time they were successful. Another seven days of hard fighting culminated in the closing of the Falasie Gap.

During September and October the Regiment joined in the pursuit of the retreating Germans into Belgium. The Regiment participated in the operations which cleared the Scheldt Estuary and in the stiff fighting along the Leopold Canal. The Germans flooded much of the lowlands and many casualties were sustained fighting along the dykes and roadways.

In October 1944 the Regiment crossed into Holland and advanced to the east of Bergen op Zoom. Finally, to close the Scheldt operations on 6 November 1944, a troop from C Squadron opened fire on four German naval vessels attempting to leave Zijpe Harbour on an island in the southwest of the Netherlands. They sank three of the German vessels and damaged a fourth. The ship’s bell was retrieved from one of these vessels; that bell currently resides in the Regiment’s Officer’s Mess.

From November 1944 until February, 1945, the First Canadian Army held its positions, preparing for the planned offensive to clear the Rhineland in Germany west of the Rhine River, then to cross the Rhine and move into Germany. During the Battle of the Rhineland in February and March 1945 the Regiment took part in the attack on the Hochwald Forest and led a flanking advance toward the town of Veen, Germany. The Regiment fought some of its most violent battles in the Rhineland, suffering heavy casualties.

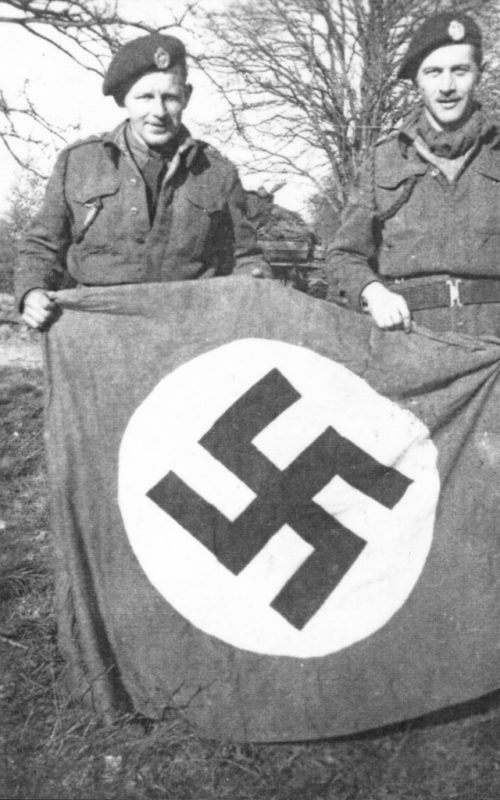

The Regiment then crossed the Rhine in April, 1945 and quickly captured the town of Neuenhaus, including many German soldiers who could not get away in time. For a few days the Regiment administered the town. A prisoner of war camp holding a large number of Russian soldiers in unspeakable conditions was also liberated.

The last major action of the 28th Canadian Armoured Regiment (BCR) began on the 17th April, 1945, when they crossed the Kusten Canal and by VE-Day on the 5th May, 1945, they had pushed the Germans back beyond Bad Zwischenahn.

The Regiment had lost 122 Officers and men killed and 213 wounded along with 105 Sherman and 14 Stuart tanks, as well as one Crusader tank during the fighting. Sixty-six decorations had been won, including 2 DSOs, 1 MBE, 3 DCMs, 5 MCs, and 10 MMs. Fourteen new battle honours were added to the Regiment’s proud record.

On the 1 February 1946, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel JW Toogood, the Regiment returned to Vancouver, and the Dukes marched through drizzling rain and cheering crowds to the Drill Hall.